Dune: Popularity

What qualities cause a work of art to be enduringly popular?

Jude: Hello! I’m Jude and I’m here with Thomas for the first of what will be a series of posts about Dune. Since Dune is science fiction, we’ll interleave these with parallel discussions of a famous fantasy book. Check out our About page for more about us and our unique format here at Story Symposium.

Later in this series we’ll be discussing in detail Dune’s plot, its desert setting, its memorable quotes, and more, but today our lead topic is popularity. What can Dune teach us about what makes a work of art enduringly popular?

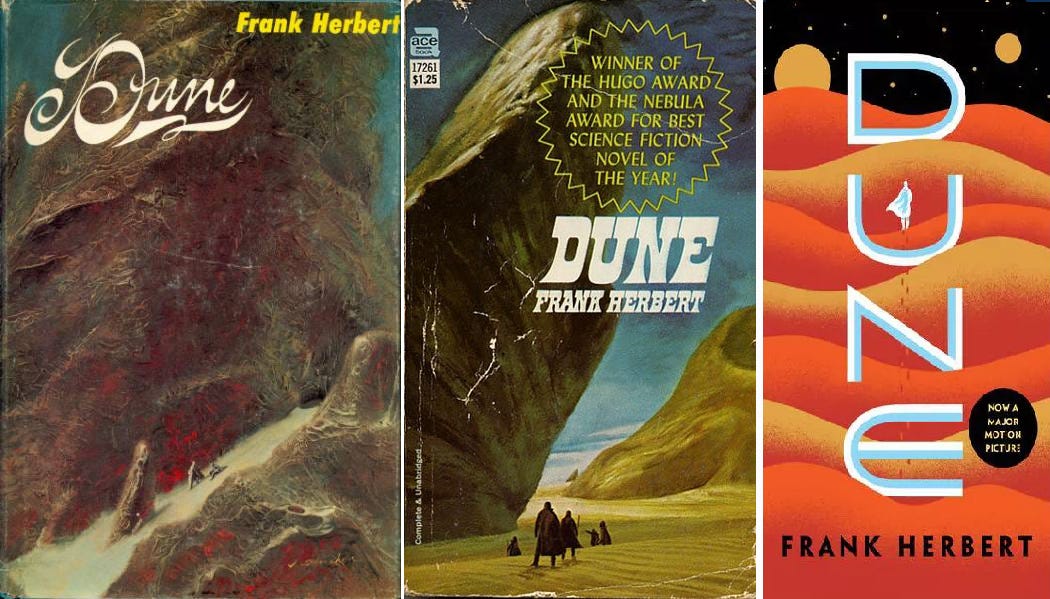

Dune is a great basis for a discussion of popularity seeing as it’s been continuously in print since it was published in 1965 and is frequently said to be the bestselling science fiction novel of all time.

Thomas: “Bestseller” is one of those words people put on nearly anything. Is there real evidence it’s sold more than any other SF novel?

Jude: Well, to be honest, I can’t find any reliable evidence this is actually the case. But people say this a lot.

Thomas: That’s not very convincing. People say a lot of dumb things, especially on the Internet. I can say that William Shatner’s TekWar is the bestselling SF book of all time but that doesn’t make it true.

Jude: And yet no one has ever said that. At least, before you did just now. So I still say that tells us something. Meanwhile there are other indicators. A lot of popular books eventually get adapted to film or television, but Dune has been adapted three different times.

Thomas: That’s true, but it would be more convincing if any of those adaptations were actually, you know, hits.

Jude: I think Villeneuve’s 2021 movie did very well considering it was released simultaneously in theaters and on streaming in the middle of the pandemic.

Thomas: It did okay. We’ll see how “part 2” fares, I guess.

Jude: Dune has also birthed a franchise of sequels and prequels, originally by Herbert himself and since his death, by his son and a co-author. Those books have continued right up to the present.

Thomas: If we’re going with “everyone says” evidence, I’ve got to point out that everyone says all of the books by his son are terrible.

Jude: I haven’t read any of them, so I can’t say how good they are. Have you read them?

Thomas: Oh, definitely not. I don’t let trivial details like that stop me from saying they’re bad, though.

Jude: Well, if they’re really terrible but still being published, someone must be buying them, and that shows that Dune is so popular there are people willing to buy more books in the franchise even though it’s been decades since a good one was published.

Thomas: Too bad we can’t get reliable statistics on this. Maybe no one has bought any of them for years and the publisher keeps putting them out as some sort of tax writeoff.

Jude: The closest thing we have to public numbers is the Goodreads rating count. That works best for comparing sales between two books published at the same time since older books have a lot more readers who didn’t use Goodreads, but it’s pretty indicative I think. Anyway, if you rank all books by Goodreads rating count, Dune comes in ninety-second. If you restrict that list to just adult SF novels, Dune comes in ninth. And I think seven of the eight books above it, books like Nineteen Eighty-Four and Frankenstein, are getting propped up by getting assigned in schools. I don’t think Dune is getting much help from teachers and professors.

Thomas: Is it really help? I would have a much higher opinion of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist if I hadn’t read it, but my ninth grade English teacher made sure I know I don’t like it.

Jude: Yeah, but unfortunately in this Goodreads rating measure of popularity, your angry one star review of Oliver Twist makes it more “popular”.

Thomas: Great metric you got there. Anyway, despite my nitpicking, I will concede that the original Dune is popular.

Jude: Thanks, that’s very generous of you. But even though it’s taken us an absurdly long time to agree on it, just saying Dune is popular isn’t that interesting. The real question is: why? I think we should start with a common sense observation: Dune is a really good book!

Thomas: That implies that anything popular is really good art, which is plainly untrue. Or, I guess, that really good art will become popular. That also seems false. Hopefully you’re going to pick one of those as your position so I can start bringing up terrible blockbuster movies, terrible pop songs, and–

Jude: No, don’t get your hopes up, I don’t think everything that’s popular is good art. I think I’d say instead that a lot of popular art is carried by the winds of the moment. It’s in tune with the zeitgeist, it’s in the right time at the right place, whatever cliché you want to use. That kind of thing is popular, but it’s here today, gone tomorrow.

If you look at the top-grossing films in America in 1980, the number two film was a movie called 9 to 5. I’m not really a film geek but I’ve never even heard of that movie. It must have been popular at the time, but it didn’t last. On the other hand, the number one film was Empire Strikes Back. That movie has been enduringly popular in a way most movies aren’t, including some more recent Star Wars movies. When something has enduring popularity, it’s speaking to different generations and cultures as people change over time. Dune has been doing that since 1965. It’s got to be doing something right.

Thomas: Maybe. But maybe it’s just got a sort of first-mover advantage. Since you brought up Star Wars, I think the original was a pretty good film, but I can’t help but notice that whenever I meet people in their twenties and thirties who didn’t see it until they were adults…they don’t think it’s that good. Maybe part of its lasting appeal is that it got itself stuck in people’s heads and didn’t leave enough room in the culture for similar films to take hold.

Jude: I guess you could try to make the first-mover argument about something like Frankenstein, which was arguably the first science fiction novel in 1818. But Dune is from 1965. It wasn’t the first mover as a science fiction novel, it was a ten-thousandth mover or something.

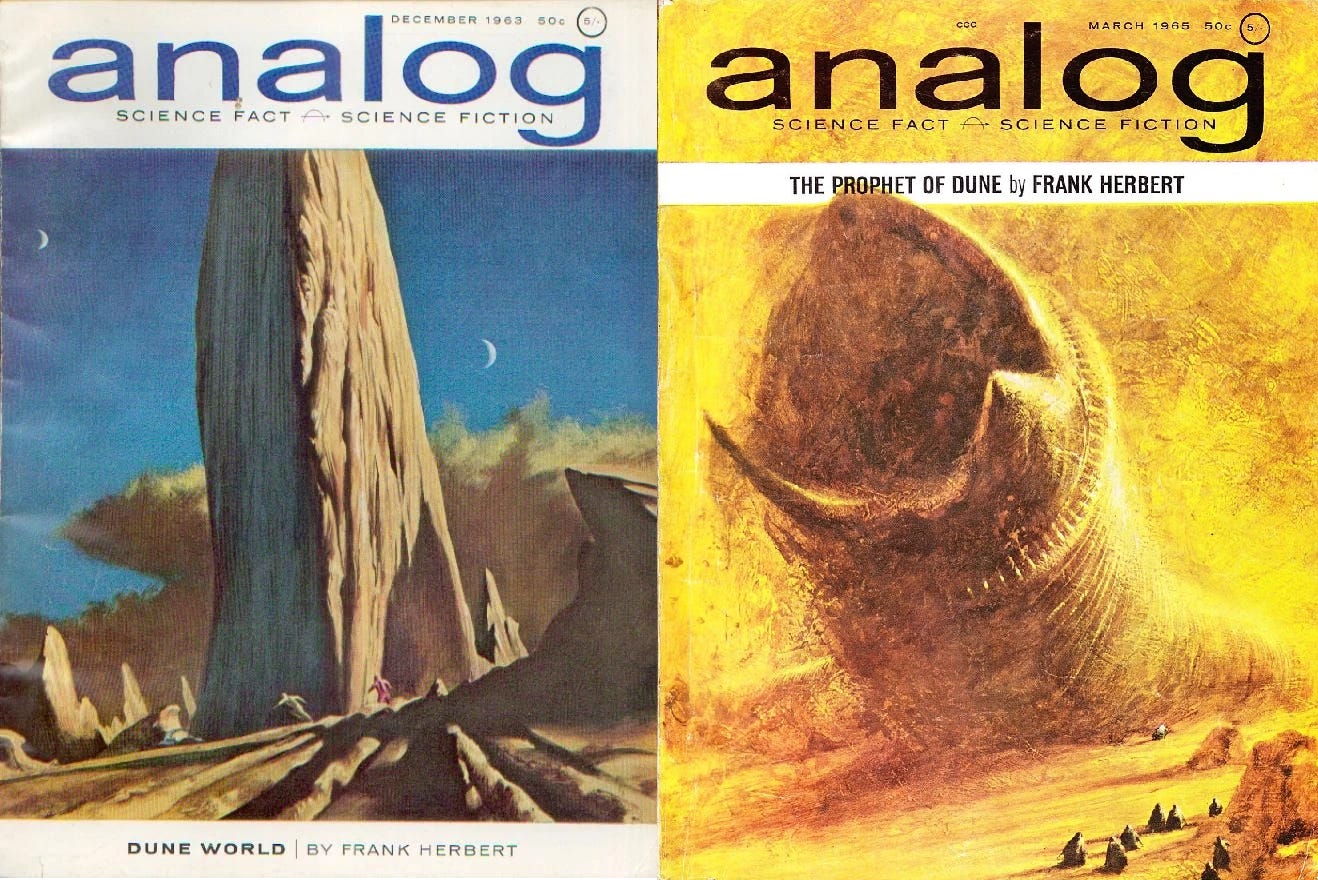

Thomas: Okay, but even though there had been novels for hundreds of years, the genre of science fiction novels was still fairly new in 1965. Frankenstein and turn of the century books like those by Jules Verne or H.G. Wells were just considered literature. Science fiction as a marketing category and an audience meaningfully separated from generic fiction is something that came from short story magazines in the early twentieth century. If you look at “classic” SF novels of the 1950s, books like Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot and Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End started out as short stories and just got fixed up into novels. The idea of genre SF intended to be a novel was still quite new in 1965.

Jude: Dune itself was published as two different serialized novellas before it was packaged into a novel. So what?

Thomas: My point is that you have to at least wonder if Dune was just good by the standards of its time, the least bad of a bad lot. That got it some justified plaudits, but then it got stuck in the cultural consciousness for the next sixty years. So it’s more “popular” than recent, better books, but that just goes to show that the best way for an author to write a popular novel is to hop in a time machine and publish their book back when far fewer books were published and the overall quality was worse.

Jude: I think you’re overstating how easy it is for a story to get “stuck” in the culture. Robert Heinlein was hugely popular and had a lasting presence for many years…but I feel like in the last twenty years his work has all but evaporated. People today can’t tolerate his politics, his treatment of gender, and so on.

Thomas: If we’re going to talk about authors whose gender ideas are worthy of cancellation, let’s talk about Frank Herbert and how he depicts Baron Harkonnen–

Jude: We will, but another day. Right now I want to posit that Dune has endured because it does so many things so well. It’s so good at so many things they are hard to list, but I’ll try to list them quickly here since we’ll cover most of them in more detail in future discussions:

It’s a relatable coming of age story

The main character, who the reader can identify with, discovers he has special powers and an important destiny

It’s an exciting space opera story that combines cool technology like spaceships and vehicles that fly by flapping their wings with old-fashioned courtly manners and duels

It’s a story that, unusually for its time, features a central female character who is powerful, capable, and sympathetic

It’s deeply interested in the lived environment of its characters to the point it has a lengthy appendix with more details about the Arrakis

It posits a complex society and actually uses sociological ideas for a major plot point

The story involves generous helpings of palace intrigue, mass politics, and economics

There’s clear historical analogues for characters, situations, and factions in the story, but these aren’t so direct that it becomes dry, predictable, or unintelligible to readers who don’t know anything about the parallels

That is a big list. I certainly am not going to say that Dune is peerless at all of those things, but where Dune really is close to peerless is just how many interests the story can connect with. You may not be interested in all of these things, or even most of them, but if one of them resonates with you that’s probably enough for you to have a positive experience with the novel. And if two or three resonate, you’re probably getting an experience few other novels can replicate.

Compare that to Heinlein. In many of his adult books, if you don’t like his politics then you’re in trouble because you have to sit through page after page of an author-insert character preaching odious politics at you. I think some readers today won’t be comfortable with, say, the portrayal of Harkonnens, but any time you get annoyed with Dune about something, you can turn the page and it’ll have moved on to something else that’s interesting in a different way.

Thomas: I agree both that your list is impressively long and that Dune isn’t peerless at all of them, but I think we should go farther and say that there are books out there that do every single one of those things better than Dune. Do you agree?

Jude: …I guess so. Probably there are individual books out there that do each individual item from the list better, but they are all different books.

Thomas: Right. I guess I can get behind a grand theory of popularity that amounts to: be great at being mediocre. Be mediocre more thoroughly than anyone else.

Jude: Hang on, “mediocre”? I need to revise what I said because I think Dune is really good at all these things. To complain it’s not the very best at any one of them is setting a really high bar. We have a lot of hindsight bias since there were hundreds of SF novels published the same year as Dune and we’ve forgotten almost all of them. Most of those books were probably worse in every respect than Dune.

Thomas: I don’t know, you can’t truly be sure without going and reading all of them.

Jude: Nope, no thanks, you can do that if you want. I’m just going to assert it. And since now we’re just quibbling over terminology, I’m think we can move on. Because if we’re asking why Dune is popular and the answer is it’s great at a lot of things–

Thomas: I’ll sign up for “it’s fairly okay at a lot of things”

Jude: –then that just moves the question to why Dune is so much better at, uh–

Thomas: Better at being fairly okay.

Jude: Better at being broadly interesting and well-rounded than nearly any other book.

Thomas: Dumb luck?

Jude: Very funny. No, I think it’s better because Frank Herbert was clearly a sort of genius. That he was an artistic genius is almost true by definition since he wrote this classic novel, but before he became a writer, he was a man who had unusually broad intellectual interests. That’s exactly the sort of person you would expect to be able to write a book that can be interesting in so many ways to so many different people.

Thomas: If Frank Herbert was this towering genius, how come your Goodreads rating thing shows a dramatic drop-off in popularity for his later Dune novels? The first sequel, Dune Messiah, has only twenty percent of the ratings that Dune does. The last sequel he wrote, Chapterhouse Dune, has five percent of Dune’s ratings. His non-Dune novels are less than half a percent, despite the fact he wrote them long after Dune made him famous and successful! It’s hardly the case that everything he wrote was popular!

I wasn’t kidding when I said dumb luck. Here’s an alternative explanation that better explains this evidence: he was a weird dude who wrote very weird books. He got lucky with this one in that it happened to be weird in a popularity-producing way, but that was an accident. He didn’t do this intentionally, or if he did intend it, he certainly never managed to do it successfully again.

Jude: Is calling him a “weird dude” supposed to be a criticism? Of course an artistic genius is going to be a little different from the rest of us. I’d say he was an artist with bold, artistic vision that he followed without worrying too much about popularity. Surely that’s the more admirable path then just pandering to the audience?

Thomas: It was Dune’s success that enabled him to quit his day job and write whatever kind of books he wanted. Are you agreeing that he got lucky with Dune’s popularity or do you think he intentionally “sold out” with Dune and then used that to finance bold, uncommercial art like White Plague and Destination: Void?

Jude: I don’t know his biography well enough to know anything about his intentions, though in his short essay “When I Was Writing Dune” he claims he was focused on the art and not the audience. What I feel safer saying, though, is that he could have just cashed in by pumping out cookie cutter clones of Dune, but he definitely didn’t do that. He wrote sequels to Dune, but they’re pretty different from Dune and even from each other. And that same artistic vision was what enabled him to write a great novel like Dune in the first place.

Thomas: You’re working hard to explain why the same author that produced a runaway success like Dune never wrote anything else that resonated with people, but I have a much simpler explanation: Dune is not popular because of Herbert, it’s popular in spite of him. As you said, there are a lot of different strands of ideas in Dune, but probably the most important one is a very cynical notion about religious movements. Paul is this charismatic religious leader for the Fremen and they love him, but it’s all a sham. The prophecies he seems to fulfill were planted in their culture by external elites, his seemingly supernatural abilities are the result of eugenics, and his emergence as a religious figure causes many, many Fremen to die or get injured in the resulting holy wars.

That’s a really interesting theme and a bold artistic vision, but it’s not the theme of a popular book. The popular art version of this is: Bad men kill Paul’s father, he escapes and becomes the destined heroic leader of the fierce but simple-minded Fremen, he leads them to victory and revenge for his father. That’s not what Herbert wanted to write, but it’s what generations of people have read in Dune.

Jude: I would say he wrote that also. What’s really amazing and maybe unique about Dune is that not only does Herbert have this wonderful breadth of themes and ideas, he positions the narrative with just enough ambiguity that two different readers can essentially read two different stories. There’s the simple white savior revenge story, yes, but the same book also has that cynical depiction of a foreign man coopting a nation of people for his own purposes.

It’s like the way children’s movies, good ones at least, will weave in jokes and other elements that only the parents understand so that both children and adults can enjoy watching the same movie together.

Thomas: That’s a good analogy, but the difference is the people who write those movies are very carefully designing them to achieve that double-vision outcome. I think with Dune it’s a complete accident. That’s why I say it was in spite of Herbert.

Jude: We can’t ever really know what’s going on in an author’s head, and we haven’t even read his biography or other things that might tell us a little about that.

Thomas: No, but I’m fine making sweeping statements based on thin evidence. It’s fun. And actually I think the evidence is pretty clear. Before Dune was published as a novel, Herbert had apparently written at least parts of Dune Messiah and Children of Dune. I think he conceived of a large arc of story that encompassed at least the broad strokes of both Dune and Dune Messiah: the rise and fall of Paul Atreides. Maybe you can also throw Children in there too, though to me it’s not nearly as cohesive as the first two.

Jude: Yes, he certainly intended Paul to eventually become a flawed or even failed leader from the start.

Thomas: Have you ever known someone prone to interrupting you when you’re trying to speak?

Jude: No, I definitely only speak with people who let me finish what I’m saying and who–

Thomas: When talking to someone like that, you have to be careful with saying complicated things. If you try to say “it seems like this, but I actually think it’s that” you might get cut off before you get to your second clause, making you sound like you think something you don’t. Or if, hypothetically, you are trying to say something ironic, you might not get enough of it out for people to to understand your point.

Jude: Okay, but what does this have to do with Frank Herbert? No one interrupted him. Supposedly twelve publishers turned Dune down.

Thomas: I think he had a long story in mind and was working on that, but he also wanted to publish his work, both because authors want their work to be read and because he wanted to get paid for his work. The first and most immediate path to publication was serializing the story in a short fiction magazine. Even serialized, magazines preferred stories to be shorter than a full novel, though. So Dune was published as two separate serialized stories, Dune World and Prophets of Dune. The boundaries are visible in the published novel. Dune World is part 1 and Prophets of Dune is the rest of the book.

Novels can vary a lot in length, but this was less true in 1965 and when publishing a novel by an unheralded author, publishers like them to be the standard length and not super-long. So Dune couldn’t be so long that it included the material in Dune Messiah that makes Herbert’s cynical spin on messiahs unmistakable. Had it not been for those limitations, Herbert might well have published it all together and Dune might never have become so popular.

Jude: Maybe. Dune Messiah wasn’t published until four years after Dune so even if some parts of it existed in early draft form, it’s not like it was ready to go.

Thomas: I don’t know the exact timeline of its writing, but apparently John W. Campbell, the legendary editor of Analog who had published Dune World and Prophets of Dune, turned down Dune Messiah. Campbell explained his decision by noting that in Dune, Leto Atreides is a helpless pawn of fate but Paul rises above this to triumph. In Campbell’s view, this triumphant agency is what science fiction fans wanted, so he considered Dune Messiah, where Paul himself is a helpless “pawn of fate”, to be a non-starter. And he was right: many readers who love Dune hit Dune Messiah like a brick wall. Some people appreciate what Herbert does with the story—I’m one of those people!—but it’s clearly more of a niche appeal.

Jude: Yes, but Dune Messiah is not a twist, it’s an elaboration of material that was already present in Dune. Many readers just don’t notice, or at least don’t focus on it when there’s so much else going on.

Thomas: Sure, and my point is that’s the secret of Dune’s success: Herbert’s true interests and intentions are being temporarily obscured. Although Paul Atreides’ story is the main manifestation of this, I think you can see it in other areas.

Another example is that Dune feels like an environmentalist story because it’s so attentive to climate and ecology. The mercantilist offworlders with their machines and mining operations see the environment as something to be fought and pillaged, whereas the spiritual Fremen humbly live as part of their larger world, deeply understanding it and adapting to it.

That’s enough that people have been reading environmental themes into Dune ever since, and it’s true that one of Herbert’s core ideas was humans as participants in, not mere bystanders to, the natural system. But whereas modern environmentalism is dominated by little-c conservative impulses, trying to save species from extinction and prevent the climate from changing too far away from the preindustrial status quo, Frank Herbert’s real interest was always in something closer to terraforming.

Jude: Yes, and again that’s right there in Dune. The Fremen live in the desert because they have to, they don’t enjoy it, and their long-term plan with Liet Kynes is to completely change the planet’s ecology. The Fremen riding sandworms is a pretty good visual metaphor for human domination of nature.

Thomas: It’s absolutely there. I’d say it’s even more clear than the flawed-messiah stuff. But not so clear that readers can’t get a more conservation-orienting reading out of it.

So I think we can combine our perspectives to sum up Dune’s path to popularity. It has an unusual number of interesting ideas in play and therefore finds ways to appeal to a lot of different people, like you said, and because it has so many ideas going in so many directions, readers can easily miss or ignore Herbert’s authorial intentions to subvert themes they enjoy.

Jude: Fair enough, there’s probably more that could be said here but I think we’ve been going on long enough. We’ll stop here before we alienate too many of our readers.

Thomas: Don’t worry, we don’t have any readers to begin with, so you can’t alienate them.

Jude: Next time, we’ll think more about popularity by diving into Lord of the Rings, then come back to Dune to discuss its protagonist and story.